What’s needed to avoid this is not individual sales but a clear media strategy

Highest number of contracts : #1- China, #2 - Korea, #3 - Taiwan

After searching I have come to the conclusion that no conclusive evidence-based report exists detailing the scale, with an exact figure, of the global anime market. However, there are sources which can be referenced to get a general idea.

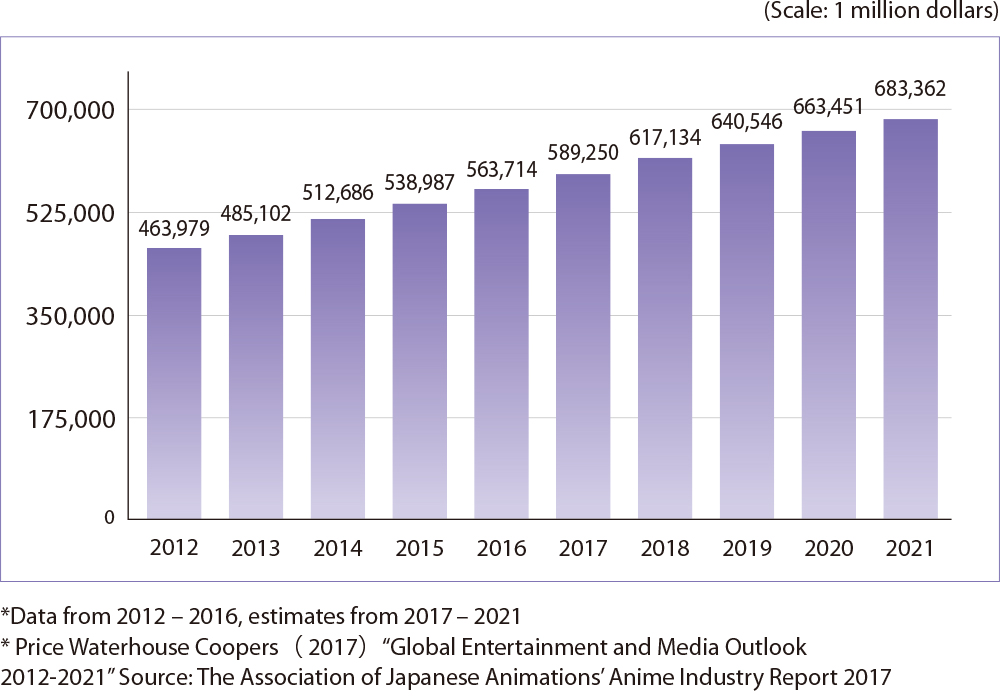

According to “Global Entertainment and Media Outlook 2012-2021” published by Price Waterhouse Coopers (PwC), the global media market value in 2016 totaled 563.7 billion dollars. (If the average exchange rate for the year is calculated at a rate of 109 yen to the dollar, this would equal 61.4 trillion yen.) [See Table 4]

[Table 4] Shift in the Global Media Market

In addition to this we have a study done by the Indian research company Digital Vector, which cannot be directly compared to the PwC study as it was conducted on a different scale, which puts the 2015 animation market value at 244 billion dollars (around 29.5 trillion yen) when factoring in machinery and industrial materials. This equals a growth of 5% in comparison to the previous year.

Then what position does this place Japanese animation at in the global market? To get a base for our reasoning on this of the place to turn for information is the Association of Japanese Animations’ (AJA) Anime Industry Report done annually. However, what is found there should be taken with a grain of salt, because the survey which this report is based on is conducted via paper surveys sent out and collected from studios which have a membership with AJA, and places particular importance on studios which have been deemed to be prime contractors. It is in no way an all-inclusive survey covering all anime titles. However, it is a good resource in which to observe a trend.

If you take the above into consideration and take a look at the AJA’s Anime Industry Report for 2017 (published in October of 2017) you will see that a ranking of those countries which entered into contracts with Japanese animation studios is as follows: #1 – China, #2 – Korea, #3 – Taiwan. The USA, which for a long period of time held the #1 spot, has fallen to #4. If you look at the contracts by region, Asia has continued to increase its hold on the percentage, occupying a total of 40% of the contracts made.

With “digital broadcasts” overseas sales hit their highest ever

The trend in global media sales shows a decrease in sales of physical media such as DVD and Blu-ray and a large-scale and steady increase in sales figures of streaming service contracts and TV channels which charge a monthly fee. Naturally, anime sales are no exception.

According to the aforementioned AJA report, digital broadcasting contract numbers stick out far above the rest. This is followed by contracts for broadcast, physical media, and then merchandise. One reason behind this that can be offered up is the quota regarding quality and quantity of foreign animations in places like China and Europe. The rules are much more lenient when it comes to digital broadcasting and paid cable compared to local TV and movie theater roadshows.

It is under these circumstances that the rate at which Japanese animation is being launched into overseas markets is picking up pace. According to calculations that I, Mori, have done based on the AJA report, the sales of Japanese animation to overseas markets reached 498 million dollars (equal to 459 billion yen) in 2016. This is the highest sales record ever seen in Japan, beating out even the DVD bubble era of 2005-2006.

In addition to this, the amount of royalties earned based on the AJA sales figures in overseas markets totals 7 trillion 676 billion yen (calculated in yen and thus not no conversion applies). As you may have guessed, this is also the highest it has ever been.

There are several reasons behind these record sales figures. (1) Hit movies such as “Your Name” and “In This Corner of the World” were met with large success overseas. (2) The number of works being produced in Japan on consignment by Chinese digital broadcasters has increased. (Details to follow) (3) Large digital distributors such as Netflix and Amazon have increased the amount they are willing to pay to purchase the digital broadcasting rights of animated works, both old and new. (Details to follow)

Will Japan become China’s “Anime-Making Factory?” within 5 years?

However, we must not be rash and bask in the blind happiness of sales being at a record high. The first point we should worry about is this one; “(2) The number of works being produced in Japan on consignment by Chinese digital broadcasters has increased.”

To put the above into perspective, this style of overseas sales no longer simply means “A Japanese production partnership funded the creation of said piece of work, which it owns the intellectual property of, and sold the digital and physical broadcasting rights to an overseas distributor.” The reason for this being that works produced in Japan on consignment by foreign distributors, meaning the distributor pays for the creation of a product for itself in a Japanese studio, are included in what is counted as overseas. Said distributors include Tencent, the media giant of digital distribution in China, as well as companies like Netflix and Amazon. (The above method of production is in fact the same style of production that has long been controversial and seen as an unequal partnership between production partnership and animation studio.)

Now of course, producing something on consignment does generate sales. It generates sales in the same way that iPhone part orders in Japan and China generate sales for their respective countries. Naturally, the product licensing of the iPhone itself does not belong to Japan. No matter how high quality of a part Japanese factors make or how hard Chinese employees work to manufacture it, the rights to the finished iPhone belong solely to Apple, Inc of the USA.

So this begs the question, can something that was produced merely on consignment and yet to which Japan does not hold the intellectual property rights really be called “Japanese animation”? We may be in the transitional period regarding this type of animation at the moment, but if we consider the next five years or so, we are sure to see a steady increase in this sort of production.

This type of production is of course one way of surviving in the global market. However, since works are being produced on consignment, a business won’t be able to continue operating independently forever. The day will suddenly come where a company overseas withdraws its orders on a decision from its home country along the reasoning that “It’ll be more cost-effective to send our orders to China.” In a way, the overseas companies will hold the life or death of domestic producers in their hands.

Thus, if we continue following along the path we are on, the day will soon come where Japanese animation studios are seen as global media production factories by China and Hollywood.

Is “DEVILMAN crybaby” something to rejoice over?

The other reason we can’t just rejoice in blind happiness is this point; “(3) Large digital distributors such as Netflix and Amazon have increased the amount they are willing to pay to purchase the digital broadcasting rights of animated works, both old and new.”

We’ll focus on “DEVILMAN crybaby” (10 episodes, all uploaded in January 2018), a series which Netflix is said to have born most of the production costs of. The majority of people applauded this as proof that Japanese animation had fully made its way into the global market. Which if you look at it from the perspective of a series directly streaming on a global media platform without using any advertising agencies or TV platforms is quite a remarkable feat. Japan also does hold the intellectual property rights of the series.

However, although this is a better situation than the one with China, it is certainly not the best it could be. Although Japan holds discretionary rights in terms of the creation of the series, it holds what amounts to no rights in terms of controlling the business side of things. Domestically, the rights to release physical media of the series are held by Aniplex, but outside of Japan the demand for physical media continues to fall and thus sales of the product in that sense can’t be said to have any real impact within Japan. So there is essentially no real income source besides digital broadcasting and no other options for earning additional income. The studio which created the series does not, however, receive any of this money paid for the digital broadcasting rights. This therefore means there are no real merits in a business sense for the studio and they are thus engaging in what could be termed “enjoyable exploitation”. Japanese animation’s strongest profit earning business model is one of earning profits in various ways, such as merchandizing, but those routes are currently in decline and may be closed off completely in the future.

There is no mistaking the fact that Netflix’s current strategy when it comes to anime pays great respect to the creativity found in Japan. However, no one knows what will happen in the future. The possibility of the company one day deciding to commission the production of popular works by American authors or authors from other regions, or of engaging in the consignment production discussed above, is not unimaginable. Indeed, the Japanese animation studio Polygon Pictures Inc. took the lead in this regard and has been doing consignment work for Disney, Hasbro and even Lucas Films for many years now. The studio honed its skills and learned how to be a powerful negotiator.

There is no denying the fact that that Netflix may decide one day change their policy and take the approach of “Why don’t we put our money into animation studios in China or other developing nations that have built up their creative skills to an acceptable level. It’ll be more cost-effective than Japan.” There is no guarantee that Japan will continue making series like “DEVILMAN crybaby” forever.

The Japanese animation industry is gradually being sucked up into the global market

When you stop and think about it, no matter how well received “DEVILMAN crybaby” is, it doesn’t change the fact that on a global scale it is merely falls into the category of being a show popular with a specific segment of anime collectors, or a “cult classic.” What it comes down to is that media geared towards kids is where the real business is at in terms of the global market. Disney, which was the first major company to build up their own TV network in Hollywood, earns over half of its revenue from its paid TV channels. That is how powerful kid-friendly content is.

The Chinese investment takes nowhere near the same lukewarm attitude as Netflix currently does. The intellectual properties belong to China and Japan is treated entirely as the production factory for its media. If this trend keeps up Japanese anime production may become internalized into the Chinese economy in itself.

It used to be that the biggest concern regarding Japanese animation was how it was going to make its way out into the world. That now has to be set to the side as the major concern is the fact that the industry is being sucked into the local industries worldwide, namely China and Hollywood. This is the same as how Japanese machinery and home electronics makers were relegated to being parts makers for products manufactured overseas with no time for worrying about overseas expansion. For all that, the makers may eventually see even this parts procurement transferred to Korea and that is not a laughing matter.

Actively engaging in the media business is imperative

The Japanese animation industry needs to look five years into the future and figure out how it can survive without repeating the same mistakes of the machinery and electronics industries.

Let me preface what I’m about to say by stating that all of this is under the assumption that the anime studios and production companies in question have enticed personnel to work at their company who have the necessary skills to compete on an international business level, which include being able to speak English and the understanding of international business practices. As the anime industry stands currently, personnel of this type are few, but if a company embraces and English speaking environment within its offices, it should have no trouble securing a young and talented force eager to enter the anime industry from southeast Asian countries.

Once the above is arranged, it should then be known that merely selling a show as a product by itself overseas will gain the industry essentially no bargaining power. What the industry needs to do is conduct its business with an awareness of the media environment in the country it is trying to engage with.

To give you one concrete example, the industry needs to secure a timeslot that airs only Japanese anime on one of the paid cable channels. That is key. Think of the TOONAMI block that was present on Cartoon Network for a time. Fill that block with Japanese anime only and you will have gained the attention of children around the world sitting in front of their TVs at that time of day.

The major thing to remember is that what is key is not selling a show as a PPV (pay per view) product, but selling a show to be streamed on a paid cable network. The best example of this in Japan would be the “nichiasa” timeslot (A block of kid-friendly programs aired on TV Asahi owned stations on Sunday mornings). In this way, the habit of watching Japanese animation will take root in children all around the world. This is very much possible if well-known Japanese animation studios partner with influential advertising agencies and major networks in the countries they are trying to expand into.

With physical media sales in most of the world in what is essentially a state of ruin, partnering with physical media distributors as was done in the in past will not lead to successful overseas expansion. What is necessary is to form partnerships with the media.

For the longest time the animation studios saw the advertisers, media and sometimes even the production partnerships themselves as both the “buyer” who placed important orders and the “enemy” who held a large portion of the copyright. However, now is the time for the studios to join hands with the ones who are both their “buyers” and their “enemies” and venture into the global market using a media strategy.

In order to prevent Japan from merely becoming an “anime factory”, and to allow Japanese animation to expand overseas while maintaining its own identity, what is needed is to secure personnel who “understand the way the media works” even more than personnel who “can produce superior animated content”. This may be the only way to keep the Japanese anime alive should it become completely entrapped in the global market.

*The article you just read is a reconstruction that took Professor Mori’s interview as a base. Parts of the article also used quotes and abstracts from the “Anime Industry Report 2017”, which Professor Mori also contributed to, in its analysis.