Anime is counted as one of the intellectual property (IP) business, but unlike other IP businesses involving patents and designs, it is not an industrial intellectual property. It is a work of literature, an important cultural media form that combines many elements found in “influential property(*)”.Due to this fact the studios, voice actors and other elements involved in the production of the animated work make up only an extremely small part of the business. The distribution of media content, merchandise licensing and even the parts of the fandom which provide no economic benefit to the business need to be looked at from a comprehensive point of view of the business.

* Influential property is intellectual property that benefits not only itself but also influences other industries related to it. As an aside, it is often confused with the economics concept of the “ripple effect” (a concept where the necessary personnel, materials, etc. to create the item are increased or decreased due to this effect) however the general idea behind it is different.

Characteristics of IP related businesses

In the manufacturing and service industries, the business transaction is formed when a payment of some sort is made for the item or service provided. If the business wants to increase profits it must either add value to the product and increase the unit price, keep the price as is and increase the amount sold, or combine a mixture of the two. On the other hand, intellectual property can be transformed for use in a variety of commodities. Another major difference is the fact that it can be mass-merchandised without an increase in the manufacturing cost. Unfortunately not many use this feature to its full advantage, but anime as an IP is still an amazing thing.

The roots of the anime business

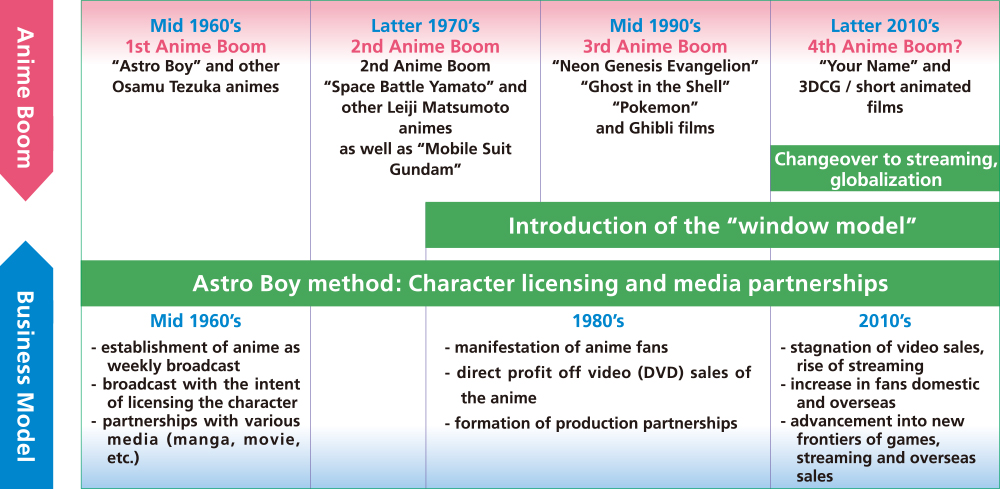

The beginning of this marvelous example of an IP business came in 1963 with the broadcast of the world’s first ever animated TV series “Astro Boy”. The business influence of “Astro Boy” didn’t stop at those directly related to its broadcast but extended to licensing everything from snacks, stationary and clothing to the development of toys based on the series, movie roadshows and manga serialization. This broad use of the intellectual property had a synergistic effect that became the irrefutable base for the anime businesses of today. Tezuka’s other series which were produced as anime following the same format as “Astro Boy”, as well as other anime series in the early days mass invested in in the same way, also experienced great success. (1st Anime Boom) [See Table 1]

[Table 1]

“Astro Boy” and the “window model”

20 years on from the birth of “Astro Boy” in a world where TV was the only medium to broadcast, the anime business had evolved and began releasing media to be viewed at home. With this release, the industry began to take on an organizational structure that could be compared with that of the U.S.A., the “window model” structure. The window model structure was a strategy of extending the life of a piece of work by first premiering it in theater, releasing it then on video, followed by paid cable broadcasts and finally broadcasting it over the air on local television. What followed was the sales and rentals of videos and laser disks of what were known as OVA (original video animation, also known as direct to disc releases overseas). With the broadcast of these OVA on the newly created midnight television hours and the profits of the OVA (in both sales and rental), the anime industry really began to feel the extended effects it was having on the market. From that time on the anime industry expanded into one where series were released on the assumption that they would follow the path of “Astro Boy” and promote a multi-media character license. The business model transformed into one that was a compound of the “window model” and one of video production and distribution. The result of this was one where even if a series “first run” (its first release onto the market) were televised, the major revenue source would come from video sales.

The dawn of the production partnership

With the declining birth rate came a decrease in the number of children per household. This brought about the removal of anime programs from the “golden timeslot” in the 90s and made the birth of the compounded business model above inevitable. The compounded business model likely played a large role in influencing teens and older who had experienced the 2nd anime boom of the 1970s becoming dedicated fans who manifested their purchasing power as well as the broadcast of animated works aimed at young adults during the midnight timeslot.

The TV stations broadcasting the shows, the studios producing them and even the advertising agencies there from start to finish were not enough to efficiently implement this sort of business model. Partnering with the sponsors who had been there from the beginning and the video manufacturers who directly earned their revenue from the viewers was of the essence. In order to meet the operational efficiency needs of the TV networks now that anime was no longer being shown during golden time and the networks could no longer afford to spearhead the production of new programs, structural organizations known as production partnerships were born. These partnerships were composed of companies skilled in their individual fields of publishing, printing, game manufacturing, licensing and other industry-related activities. These partnerships produced, became sponsors of and in the end held the rights to the product as its commissioning entity.

Production partnerships of this type are unique to Japan. They use television and other media as a base to invoke a sense of existence of their product on a multitude of levels. This in turn creates a synergetic effect that leads to securing fans and stimulates their buying power. Though the industry has up until now used production partnerships as its base, the anime business model is now seeing itself further evolve. This evolution is due to changes in the domestic and overseas video streaming industry, the guarantee of profits from non-picture domains like game production, and the participation of overseas businesses in production partnerships both directly and indirectly.

The core of the anime business

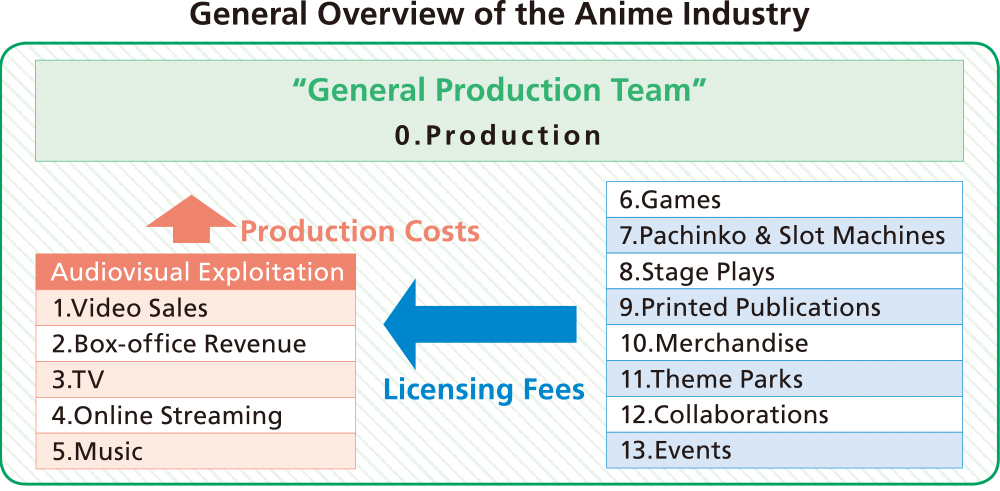

The anime industry as a general rule can be broken down into three structural parts. [See Table 2]

[Table 2]

All of the businesses directly related to the production of the work itself make up the majority of the “General Production Team” (=income that goes to the anime studios, etc.) section of part (0) on the Anime Industry Report put out by The Association of Japanese Animations.

Next you have the businesses that make up the core of the industry in sections (1) through (5). These are added to in accordance with the evolution of media forms and over time redefine what the mainstream is. The main point to keep in mind though is that these media forms operate concurrently. I brought up the “window model” before that is prevalent in the U.S.A. which sees movie theater release as its source. Anime, on the other hand, sees TV broadcast as its source. However, it follows the same idea of releasing to different media forms gradually in chronological order to best respond to relevant operating risks. The difference in the West is that the “contents business”, as it is called, has specialized itself in businesses related directly to the moving-picture media form itself. The producers themselves (who are the rights holders) take care of everything and their investment-return is taken care of entirely within the moving-picture media business. If the film or other media does well, then product licensing, etc. may perhaps come into play. The one exception to this is Walt Disney Co. of the U.S.A. which engaged in a variety of developmental means (known as franchising) and now boasts media networks and theme parks all around the world. The unparalleled power said company eventually came to hold is a testament to the anime business style in Japan that doesn’t limit itself to moving-pictures only.

The distinguishing feature of the Japanese anime industry since the days of “Astro Boy” has been a business model where the intellectual property of the anime itself generated monetary income to the producers themselves (as seen in (6)-(13). However, as pointed out previously, in international markets this sort of licensing is merely something “extra” that may or may not occur. In the case of anime production partnerships, the relationship between the anime itself and the businesses spawned off of it do not necessarily as a master-servant relationship. To the revenue generated by companies in (1)-(5) (which handle broadcasting, box office sales, advertising, physical media sales, streaming, etc) is added that of the production team in (0) and the related businesses in (6)-(13). It is becoming increasingly common that the production partnership does not see investment-return as likely through sales of the anime itself and places its main focus on the income it can earn through sales of related games and licensing to overseas markets. Consequently the way in which the IP is used by (6)-(13) typically has the quality of said use closely managed and any usage that goes against the producers intentions is strictly forbidden.

What is described above is what is represented in “General Overview of the Anime Industry” as part of the Anime Industry Report put out by The Association of Japanese Animations. It shows that the total figure generated by all three of the structural parts above is the amount expended by stakeholders (and businesses) in the production of an animated work and the licensing of its merchandise.

The extent of the anime business

However, it is likely that many would feel that something were out of place if the above “General Overview of the Anime Industry” were presented as the measure of what anime is socioeconomically. The easiest way to explain it is that what we see in the above “Overview” is what came about as the natural economic conclusion of the several anime boom periods seen in [Table 1]. You may have noticed that those boom periods are referenced nowhere in said overview. The reason being that a boom period itself does not reflect back economically (meaning it provides no social or economic benefits) to the production team. It also contains economic activity that is difficult to perceive (i.e. its own non-economic domain) and yet incredibly important to the anime industry.

The power of networking

To many, anime is a form of media content that can be viewed for free on broadcast TV. Due to this fact there are many passionate fans who, while they may not contribute through monetary purchases, bring the topic up in conversation. If the anime then becomes a common conversation topic, those who are unfamiliar with it may learn more about it and begin actively watching it themselves. This is what is called networking (or externalization). As a result, viewer numbers increase and said viewers’ interest may lead back to contributing monetarily to the producers (internalization) via product purchases and other money spent in relation to that anime. Animated works would not see the amount of success they do without the involvement of these peripheral processes.

In most cases, economic activity by fans for fans such as the publication of fanzines and cosplay, along with reproduction and re-creation of existing series, contributes in no way economically to neither the producers of the work nor the periphery businesses involved. However, these aforementioned works wouldn’t exist if the fans had not already been willing to spend money on products and services already in existence. In this way the periphery businesses see an increase in their profit opportunities, which in turn leads to more people learning about those businesses through mass and social media. This in turn leads to more people spending their money and another wave of the network effect occurring. One recent example of this you may recall is when Walt Disney Co., a company normally very strict when it comes to keeping legal control of their properties, encouraged fans to upload videos of themselves singing the theme song of the movie “Frozen” (“Let it Go”). This gave rise to a huge degree of popularity that led to the movie’s success.

In this way, the anime industry holds its works at the core and those works make up something superb, a business which embraces the unique model of indiscriminately involving paid, unpaid and even third-party elements. The complete picture of what it is is enormous and is almost never accurately spoken about.

An ecosystem made up economic and non-economic factors

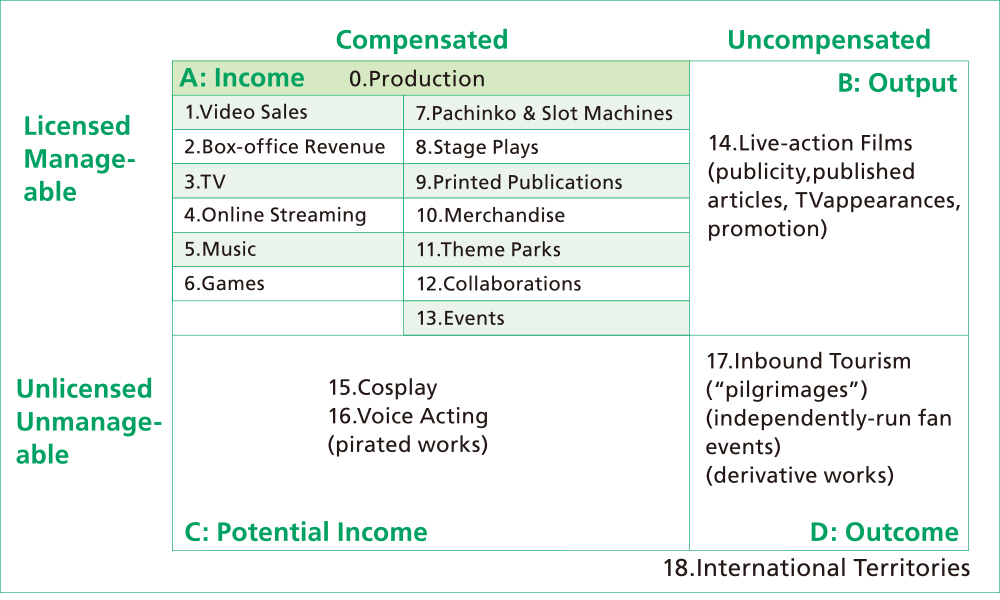

As previously discussed, in addition to the picture broadcasting business elements the producer (i.e. license holder) directly engages in, there are numerous periphery businesses which are compensated and licensed to be so. There are also licenses granted in which compensation is not part of the deal. If we add into this outside businesses and fan events conducted without compensation and/or without consent, then we can see just how extremely large the anime business is. If we break these business elements down into those that provide or do not provide compensation to the producer, combined with whether or not each is licensed, then we can begin to get a complete picture of what the anime business entails. [See Table 3]

(“pilgrimages”)

(independently-run fan events)

(derivative works)

[Table 3]

(A) Compensated Manageable

This what falls into the fields of the aforementioned “General Overview of the Anime Industry” and involves the production (which may be a production partnership) itself and the businesses granted a direct license. Things that fall under this domain of economic activities are such as the production studio that made the anime. Everything within this domain falls under the category of income that was expected in accordance with the production of the work.

(B) Uncompensated Manageable

This category involves those periphery businesses which carry out activities that increase the popularity of a product, thus increasing the scale of (A), but are not accompanied by the exchange of money. These activities may involve published articles or introductions on TV programs that act as part of the PR strategy of the production team and introduce the work in a way that reflects the production team’s intent. In some cases, the production team may pay for that promotion in order to have the coverage completely reflect the intent of said production team. On a more unbiased side, informational and other journalistic publications may decide to focus on an anime or themes related to the anime in their publication. All of the above form the peripheral media business that is part of the industry. The live action films mentioned in (14) are often realized through a direct contract with the original creator of the work, often the manga artist, and whether or not the anime production side receives payment of any type is determined on a case by case basis. There is also a high probability that the work created will be not in accord with anime production team’s vision. Be that the case, there is still an expectation that the marketing of a live action film will have a synergistic effect on the anime, thus placing it in this category. Everything found in this category can be considered something that will greatly increase the impact an anime will have and can be thought of as “output”.

(C) Compensated(possibly) Unmanageable

Those sales channels which form and take advantage of the popularity of a work, but have not established a license nor engaged in any compensation agreement with the original production team (i.e. pirated works that have income potential), fall into this category. The TV sponsors (advertisers unassociated with the original production), equipment providers and cooperative entities on location also fall into this category as they are part of the commercial media and yet not required to pay any compensation to the production team. In addition to the above you also have (15) fan-made cosplay and (16) other stage and television works done by the voice actors. Both clearly have influence on how the produced anime is perceived but it is very rare that a production team ask for payment or to be able to oversee these endeavors. It could be said that the aforementioned sometimes fall into a category that is close to that of the “publicity” discussed in (B).

(D) Uncompensated Unmanageable

The works in (D) resemble those of (C), but differ in one major way; the production team does not require consent and even if it were practical to claim compensation, it would not choose to do so. If anything, this category (which includes fanzines, independent fan-run events and derivative works) strengthens the fondness fans have for the original work. (17) Inbound tourism and study that is motivated by a person’s love for an anime, also falls into this category.

The rapid growth of the tourist economy from this inbound tourism holds great significance to the Japanese economy. However the reality is that even “pilgrimages” by domestic fans of an anime, although they have an economic effect on the public transportation services and other travel services which get them to their destination, do not provide a profit to the majority of the “pilgrimage areas” unless the areas work hard to develop a scheme to do so. In the first place, the setting of an anime becoming a “pilgrimage area” is something completely unexpected in most cases. On top of the fact that you cannot count on locations being a featured aspect of a piece of work, nothing will happen unless the crucial work that is being discussed becomes extremely popular. Saying that, the reality is that people are making “pilgrimages” and people are coming to visit Japan after being charmed by Japanese animation.

What the above all have in common is that despite the fact that the results may not always reflect the intent of the anime production team, some sort of “outcome” is produced as a direct result of the fandom’s enthusiasm. The fact that this enthusiasm cannot be controlled and yet can have such a great impact is indeed troublesome. And yet, the animated works that have been created as a direct result of it, as well as the fanzines and inbound tourism which were created by the existence of the industry itself, can no longer be ignored.

What is generally called the “anime industry” refers to those elements found in (A) that have a clearly defined value for the production team, reflect definitively the will of said team and in which the expected profits are generated (the aforementioned “income”). However, in order to heighten the effect influential properties such as those elements of (B) have, it is necessary to engage in interactions with the entire anime community through a variety of means (to create “output”). Some of those means may involve a form of compensation being paid to periphery businesses by the production team itself. I am sure that we can all easily agree that interactions which involve expenditures by the production team itself fall under the economic sphere of the anime, but the fact that it doesn’t stop there is what makes the anime industry special. What I mean by this statement is that both the legal and illegal economic activity that springs up surrounding the fandom (C:Potential Income), as well as the activities which exist on a non-economic basis (D:Outcome) are tolerated. This is due to the intuitive recognition that it is important to promote a sense of trust and anticipation with those fans for the long-term.

All of this is that the current economic state of the anime industry is a cumulative result of uncompensated and un-regulated factors going on behind the scenes. These factors form a firm base on which choose to create their own vague homages to the anime industry or even choose to enter into the industry themselves. A representation close to this can be found in the rapid growth that has manifested itself in the (18) foreign market over the past several years.

These unlicensed and non-economical features seen in (C) and (D), and the understanding of the community they represent, have grown to be viewed as important in the fields of media research and brand marketing. What once was ignored is now being understood by the overall industry as something that can no longer be ignored due to a betterment in the understanding of how it can influence companies and products. The industry is realizing how its relationship with fans and the usage of social media as part of its distribution infrastructure are key in this day and age. The tendency to conduct business with a relationship with fans as one of the prerequisites has grown stronger ever since the 2nd Anime Boom. The relationship between the industry and its fans is no longer one of “giver and receiver” but rather something more organic. It has grown into an industry where theaters and event organizers naturally take users’ needs into consideration, which has led to the development of a voice acting market as well as interactive 2.5D musicals.

Anime does not exist as a product by itself, but rather as an ecosystem of the relationship between the production team, fans and periphery businesses that has been actively forged. This ecosystem allows for the multifaceted distribution channels to co-exist in harmony with the product itself.

What the future holds

To sum up what has been discussed in this feature, the anime industry is not made up merely of what is found in section (A) of the “General Overview of the Anime Industry” table. It also involves the related (B) and (C), where some sort of economic benefit can be assumed to a degree, as well as (D), where one cannot. What I have tried to depict is the idea that the anime industry is not an intellectual business in the simple sense, but rather a thing which now exists as a place where the creativity of fans is expected and a fountainhead of communication among fans.

With the rise of platforms offering digital broadcasting worldwide and the movement of the domestic market in China, it is incredibly difficult to try and isolate this ecosystem. As shown in this feature, if the Japanese anime industry keeps in mind the fact that the industry is built on this organic relationship between it and its surrounding industries (that include fan communities, fanzines, etc.), then it should be easy for it to take heed of global trends and grow to be difficult to dismantle.

For all that has been said, there is the possibility that in the long-term the anime industry will share the same fate as the shrinking Japanese economy. Despite this possibility, my hope is that the industry will be able to charm more and more of the world’s animation fans by going with the flow of the tide while at the same time keeping the world at arm’s length in a way. To do this it must make it known to the world that the anime industry is not just a moving-picture business but rather part of a dynamic ecosystem. Creating an environment where this ecosystem can be enjoyed worldwide is the key to creating a bright future for the anime industry.